So, what would a mid-14th century knight or man-at-arms wear into battle?

I urge you to first watch this video titled "How a man shall be armed" which has been prepared by La Belle Compagnie, a Hundred Years' War reenacting group that has done some remarkable research. The armor that we will be making will be most similar to the armor worn by the man on the left from 1337, the start of the Hundred Years' War.

Helmet: Nothing says medieval armor like an awesome helmet. For the mid 14th century, you have a few options. If you are planning on making the helm yourself, the simplest option is to make a great helm. By the mid 14th century, the great helm was going out of fashion, but they could still be seen on the field. Great helms have the main advantage of being simple and requiring minimal tools to make. They also look pretty cool. However, they have the disadvantage of having limited visibility and of presenting flat striking surfaces (not all of them do this). An example of a nice great helm is worn by the fighter who is facing us in the first image of this forum thread: http://forums.armourarchive.org/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=85680.

The most popular style of helm is the bascinet, which is seen in the video linked above. These were initially worn underneath great helms, but ultimately they developed into a helmet of their own. They initially did not have any form of face protection, but visors and nasals developed quickly afterwards. In the SCA these are often made as a fairly cheap starter helmet and face protection is carried out by welding steel bars together to make a "basket" for the face. As far as making these yourself, they aren't terribly difficult, but do require some more tools than the great helm, are a little more difficult to shape, and require access to welding equipment. If you are going to buy a helmet, this is probably your best bet.

A third option is the kettle helm. I won't go into much detail about them, but essentially they are a steel wide-brimmed hat. Medieval kettle helms lacked face or side protection, but SCA versions typically include a bar grill and some metal slats to met the minimum armor standards. These are about the same difficulty to make as a bascinet, but have a few more pieces, so they're a bit more expensive to buy.

Choosing between these helm styles will largely be a question of aesthetics. In general, I recommend simply buying your helmet, as making your own requires some metalworking skill, access to materials and tools, and will take a relatively long time to complete on your own.

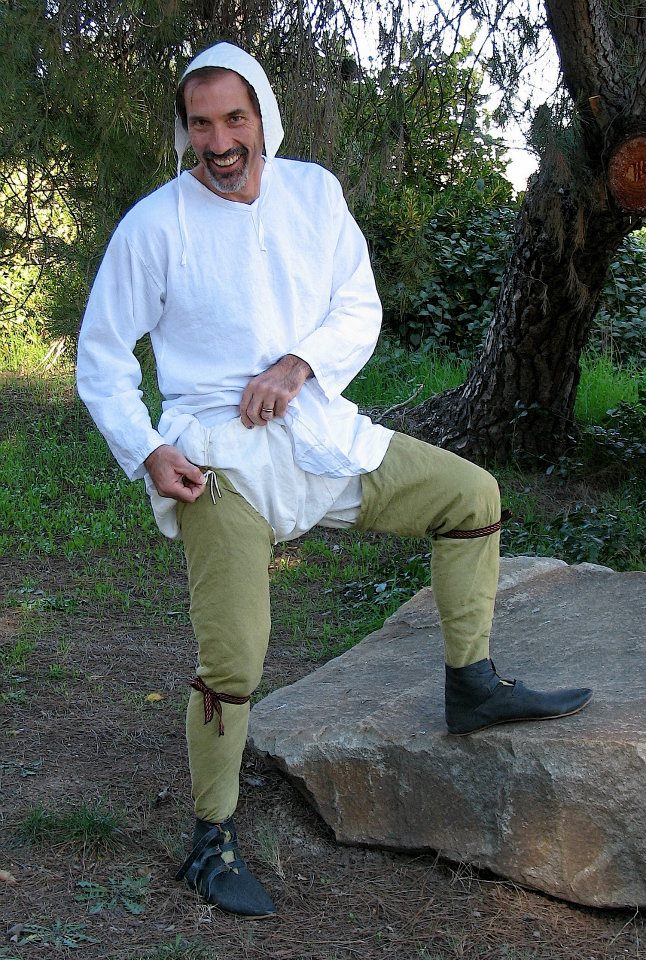

Padding: The first layer of any armor is typically padding that serves to cushion the body against blows, provide a place to attach other pieces of armor, and make wearing armor more comfortable. Typically padding was made from cloth, with a natural undyed or bleached linen outer shell that is padded by either stuffing some form of material into channels stitched into the fabric or by quilting layers of thick material between the layers of the shell. Historically the stuffing would be a natural material, and I urge you to do the same. When armor was stuffed, materials like un-spun wool, horse hair, and raw cotton were used. If you use the quilting method where you stitch multiple layers of fabric together, this would be accomplished by using many layers of linen or 1-2 layers of fulled wool. Interestingly the padded layers actually offered significant protection from arrows, as layered cloth is fairly puncture resistant, and raw cotton in particular seems to wind itself around the shaft of arrows that spin as they pass through the padding. I have had success using fulled wool to pad my 16th century arming doublet. Wool serves as a very breathable layer of padding. In addition to the materials I've listed here, bamboo quilt batting also works quite well.

Depending on how you count, there are 2 or 3 different padded garments that you will want to create. The first is a garment that is sometimes called a gambeson or aketon and protects the torso. The construction of this garment is similar to the Bocksten man tunic. The second garment you'll want are padded cuisses. These cover the upper leg and also serve as a place to attach the knee cop. Building these two garments first is probably your best bet, as all of the rest of your armor will fit over top of your padding and/or will be attached to it. The third padded piece goes inside your helmet and serves as padding for your head.

Elbows and Knees:

SCA armor standards require that you protect both your elbows and knees with rigid protection. For the purposes of this suit of armor, we will accomplish this with simple elbow and knee cops that do not have any lames and does not involve any articulation. This will keep it simple and keep costs down. Making elbow and knee cops isn't particularly hard, and for many new armorers, they are their first piece, so making them is definitely an option, however these aren't usually terribly expensive pieces to simply buy either. Depending on your willingness to shape metal and your overall budget, you may consider simply buying these pieces. Once you have made or bought them, they will be attached to the sleeves of your padded gambeson and to your padded cuisses. This will help keep them in place. You will also usually need to add a strap that will go around the joint to keep the cop in place.

Wrist and Hands:

If you are planning on fighting with sword and shield, the cheapest way to protect your hands is to wear demi gauntlets (that protect the wrist and hand, but not the fingers) and put a basket hilt on your sword and shield (to protect your fingers). If you plan on using two-handed weapons (great sword, spear, polearm), you'll need full gauntlets that protect your fingers too. This gets expensive, there's really not a great way around that. Demi gauntlets are harder to make than elbows, but they're not too difficult. Getting fingers and thumbs to articulate correctly, however, is fairly tricky, so you're probably going to end up buying gauntlets.What's more is that protecting your hands is really important. It's fairly easy to break a finger in SCA combat, and since most people work with their hands, that's not really something you want. Hockey gloves are the bare minimum protection required by the rules, but they're really marginal in their protection. Fighting with them, especially sparring with pole arm or great sword while wearing them, is asking for broken fingers. Don't skimp on your hands.

Legs and Arms:

Armor for your legs and arms is optional, but highly recommended. The simplest and cheapest way of armoring these body parts is using splinted armor. Splinted armor takes the form of metal splints riveted or sewn to a leather or cloth backing. This method keeps the amount of metal shaping to a minimum and is a fairly forgiving and flexible method of armoring your limbs. As far as limb armor goes, the forearms (vambraces) are the most important part to armor followed by the upper leg (cuisses). Upper arm protection (rerebraces) are also a good idea. Lower leg protection (greaves) can also be useful. Striking below the knee does not count as a legal blow in SCA fighting, but it happens sometimes and it hurts. Splinted greaves will also improve your appearance.

Neck:

Neck protection is required. At a minimum you will need to attach a chain maille drape to your helm. However, in my opinion, this is a very poor method of protecting against thrusts which are highly prevalent on the melee field. I recommend that you also wear a gorget to protect your throat. Gorgets don't really exist in the mid 14th century, however you can make a simple gorget in the same way that you make a coat of plates. While it is inaccurate, it will aesthetically match the armor. Furthermore, if you wear a chainmaille (or leather or quilted cloth) drape from your helmet, the gorget will be hidden.

Body:

The SCA requires that you protect your kidneys with a minimum of thick leather. Some people do this using a weight lifting belt. If you have finished your gambeson, you can put on a leather belt underneath to protect your kidneys, and that will serve as sufficient armor to meet the rule requirements, but I don't recommend it. Historically the body's main protection would have been chain maille, however during the mid 14th century, coats of plates started to be worn. You can see an example of a coat of plates in the video above. Essentially this is constructed by riveting overlapping plates of metal to a leather or cloth coat. This provides rigid protection for your torso and serves as kidney protection.

Shield:

The appropriate style of shield for the mid 14th century is a "heater." Aluminum is a popular choice for making shields in the SCA because it is light, but they are also expensive to buy. Some people use street signs to make them, but this method still requires that you affix some form of edging on your shield. A more attractive, cheaper, and more attractive method is to make a bent plywood shield.